The following is a write-up of the most recent episode of the Middleweight Politics podcast.

You can listen to the full episode via the player below, or on Spotify and Apple Podcasts

.

When I think of Mike Johnson’s position as Speaker of the House, I can’t help but think of a salmon swimming upstream to spawn - struggling against currents and avoiding the jaws of grizzly bears only to get to his final destination and die.

Over the past few weeks, House Republicans have seen their majority shrink to one vote as two members - Ken Buck of Colorado and Mike Gallagher of Wisconsin - appeared to be enjoying their time on the Hill so much that they opted to retire early and leave their seats vacant for the remainder of their terms.

This leaves Johnson with one of two options:

Get 100% of House Republicans to agree on legislation they can pass on a party-line vote.

Negotiate with Democrats to pass legislation and be ousted from his position as Speaker.

Given that Georgia Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene has already filed a motion to vacate, it seems the first option might be off the table.

Johnson’s problems containing his caucus don’t stop at the House floor. Despite calls from GOP leadership for party unity, Matt Gaetz has endorsed several ultra-conservative primary challengers to incumbents supported by former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. One of these incumbents is Texas Republican Tony Gonzalez, who voted in favor of a bipartisan gun control bill after the school shooting in Uvalde - a town in his district.

Democrats aren’t immune from this problem either. Reporting by Politico revealed how Democrat turned Independent Senator Kyrsten Sinema was targeted by progressive donors over their frustration with her tendency to buck the party line on issues such as filibuster reform and increasing the minimum wage.

American Israeli Public Affairs Committee (also known as AIPAC) and liberal activists have clashed over AIPAC’s allocation of $100 million to primary challengers against Democrats they view as insufficiently supportive of Israel’s military operations in Gaza. These Democrats are almost exclusively in the party’s left flank.

It would be easy to write this off as your run-of-the-mill dysfunction in Washington, however, it ignores that this is part of a larger global trend. Every Western democracy has seen a rise in polarization and political fragmentation.

What makes the United States different is that our system forces what should arguably be four or more parties into two and, in doing so, runs the risk of letting more extreme political minorities dominate the process.

Things Falling Apart

Earlier last year, Pippa Norris of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government published a paper entitled “Things Fall Apart, The Center Cannot Hold”, which documented how, since the 1960s, the political landscape in most Western democracies has become more fragmented and polarized.

Like the US, all Western democracies have seen a rise in populism and polarization over the past 20 years. In most countries in the study, this has led to an increase in the number of political parties - with the average rising from 3.5 in the 1960s to 5.1 in the last decade.

In the United States, this has resulted in two parties that don’t get along well with their own members, much less the other side.

Many have argued that, while America’s two-party system has its drawbacks, it also brings an element of stability by crowding more extreme ideologies out. But is that the case?

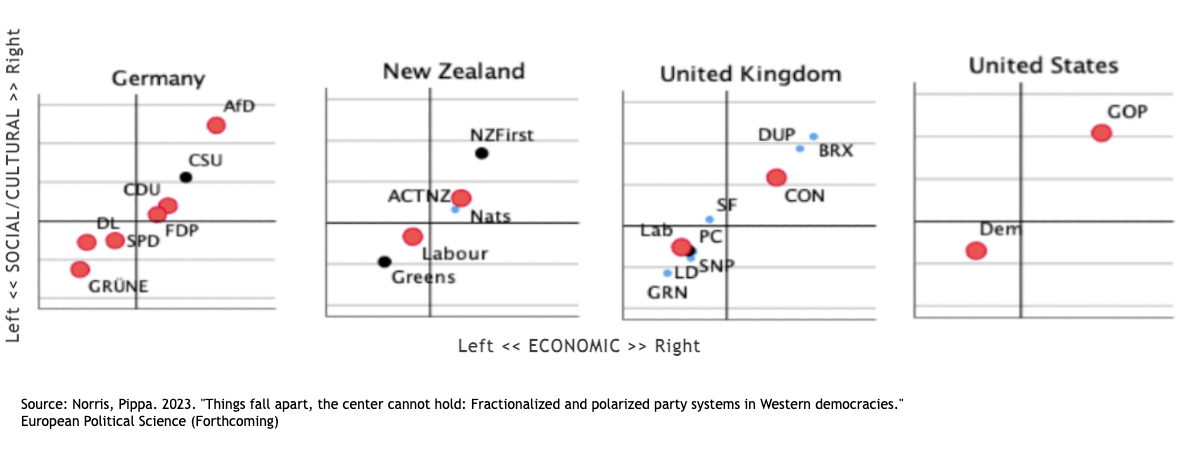

In her paper, Norris maps out the ideological landscape of 24 countries based on where their parties stand on economic and social issues. In the chart below, the x-axis shows where these parties stand on economic issues (further to the right being more conservative) and the y-axis shows their stances on social issues (further to the top being more authoritarian/populist).

What we see in the first three examples are systems with major center-right and center-left parties and parties occupying the far-left and far-right quadrants. In the case of the United States, the center-right and far-left aren’t represented.

Effectively, the US has a Democratic Party representing the center-left, and a Republican Party that aligns more with nationalist parties with platforms largely built around nativism and an aversion to the multilateralism of the last 70 years.

This aligns with research by Pew, which shows that, while the Democratic Party has swung more to the left over the last 50 years, the GOP swung over 3X more to the right.

So, rather than preventing parties with extreme ideologies from entering into the political mainstream, America’s two-party system has made it so they’re one of our only two choices.

Why Here?

The uniqueness of America’s two-party system is directly tied to the uniqueness of how we elect people to office. In most Western democracies, seats in government are awarded based on a party’s share of the popular vote.

In Germany, for instance, the far-right Alternative for Germany and far-left Green Party won roughly 10% and 14% of the popular vote respectively, and hold roughly the same percentage of seats in government.

This is accomplished, in part, by using multi-member districts.

The US House of Representatives is comprised of representatives from single-member districts with winner-take-all elections - meaning voters are represented by the one candidate who receives the largest number of votes in a district’s election.

This system presents a few problems.

The first is that many voters are shut out of the process. In my home state of Massachusetts, 30% of voters cast ballots for Republicans in the 2022 midterms, yet 100% of the state’s 9-member congressional delegation are Democrats.

In the average congressional district, 40% of voters cast ballots for the losing candidate - approximately 44 million voters in the most recent midterm elections, and 64 million in 2020.

The second is that it’s far too easy for parties to gerrymander districts in their favor. A 5% majority is all that’s needed for a district to be considered non-competitive, making the primary of the majority party more important than the general election in determining who takes office.

In party primaries, the question becomes which type of Democrat or Republican best represents the 55-60% of voters that comprise a majority in the district, rather than which candidate represents the consensus opinion of all the voters they serve.

Norris’s study shows this has resulted in center-left Democrats and far-left Republicans gaining hold of their respective parties at the expense of the far-left and center-right.

If you take the controversial view that all voters should be represented in Washington, a bill recently introduced to Congress could change this.

The Fair Representation Act would change House elections to be more like those in other democracies, where a party’s share of seats in the House is equal to that party’s share of the popular vote.

Under the act, single-member districts would be replaced by districts with 3 representatives each. In states where the delegations can’t be neatly divided by three, at-large representatives would be elected to make up the remainder.

This would reduce the ability for parties to carve non-competitive districts, as a majority of over 66% would be needed. It would also ensure that the 40% of Americans in the minority party of their district would have the power to elect a candidate who best represents their views.

It would also make it easier for smaller parties to form, as a candidate representing a third of voters could take office. In an era of party fragmentation where the divides within America’s two major parties are sharper, the center-right and far-left could be represented alongside the center-left and far-right.

In the context of the current Congress, this would give Speaker of the House Mike Johnson more flexibility to negotiate with the center-left on aid to Ukraine and government funding, while still being able to build coalitions with the MAGA wing on issues where they’re aligned - such as immigration reform.

In what is a historically unproductive Congress, this bill faces long odds of being passed. That being said, the passage of the 17th and 19th Amendments - which allowed for the direct election of senators and gave women the right to vote - show that ordinary voters can have an impact when they organize and take action.

Two of my favorite organizations pushing for this are Fix Our House and FairVote. I’d encourage you to check them out if you’re interested in learning more.

The alternative is continuing to swim upstream.